Unit 11: Film Studies- Final Essay

Does Martin Scorsese Represent Fragile Masculinity With Regards To Laura Mulvey's A

"Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" and Aspects of Freudian Theories of Psychoanalysis in "Goodfellas" and "The Wolf of Wall Street"?

Martin Scorsese, regarded by many as "the greatest living director" (Ricky Gervais, 2020), has always remained true to his sense of self, or auteur approach, within his productions, setting him aside from the norms of Hollywood and breaking the rules of cinema frequently in his productions; in his own rights, Scorsese helped to pave the way for young, aspiring directors and still inspires many to this day. However, many of Scorsese's works have been critisesed for their diminishing view on women, and the deeper messages of both disrespect and insecurity that this conveys. Two films which particularly stood out to me when breaching this subject, for completely adverse reasons, were "Goodfellas" and "The Wolf of Wall Street", both of which I feel contain the true essence of fragile masculinity, both openly and subversively through their narratives and through the perception we are given as an audience by Scorsese of the point characters, Jordan Belfort and Henry Hill. The two films differ hugely, both in message and in narrative, with "Goodfellas" staying true to the classic Scorsese gangster film following the making of Henry Hill, and "The Wolf of Wall Street" envisioning Jordan Belfort, a true king of swindling and self made billionaire through his rise and fall in New York's befamed stock exchange market on Wall Street, however, the similarity they both possess is the blatant mistreatment and overshadowing of the point female characters in their plots; whether this interpretation was intended by Scorsese through his direction is unclear, however I find that many traits shown by male point characters within both films clearly convey insecurity and unsettlement within their personalities, thus causing the beratement we see defined onscreen.

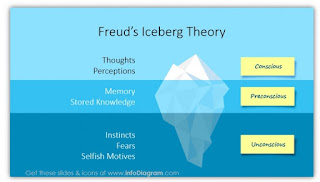

"The Wolf of Wall Street" is highly praised and critically acclaimed for it's stark truth and blatant disregard to sticking to the norms of what we'd usually see in a high budget production; the first view of "wolf" is always a shock to the system, making no bones about displaying the affects of corruption and abuse of trust in power and wealth, adorned with graphic sex scenes, drug taking, prostitution, money laundering and violence, whilst also making the audience want to be Jordan Belfort in a perculiarly glorifying manner. Scorsese's treatment of Belfort's story has come under fire for it's hendonistic depictions of fraud, manipulation and the marginalisation of women. "While "Wolf" is based on a true story and real characters, there is a fine line between accurately depicting the rampant objectification of women and actually succumbing to it"(Moira Herbst, 2014). From the outset, the depiction of women as objects is evident, with the opening sequence even featuring Jordan's wife giving him a blowjob in his white ferrari and from the outlining of his early career in wall street where he enters a room full of male stockbrokers, perhaps suggesting that this world that Jordan has found himself in is a man's world. "The male gaze plays a role in emphasising the power of men and the submissive role of women in the world of Wall Street. Women are objectified and made submissive to the male centred universe of power." (Samantha Lazar, 2017) I feel that the character who defines this submission and objectification continually throughout the film is Naomi, Jordan's second wife. From the scene where we first meet Naomi at Jordan's house party, we are presented with an almost barbie perfect woman, blonde, thin and wearing a short and tight cut-out mini dress drawing attention to her cleavage. Described as "the hottest blonde ever"(Terence Winter, 2012) in the script by Scorsese and Terence Winter, and with time appearing to stand still as the camera catches her in a medium close up shot, the audience is invited to dwell upon this constructed image of a perfect woman. This could be considered to be linked to the male gaze, which is a concept from film theorist Laura Mulvey's 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' (1975) , as we are seeing Naomi in the predominantly heterosexual male perspective and we are invited in this scene to look at her as nothing more than an object of sexual desire by Scorsese, as she offers little substance to the scene itself other than an impression of her beauty. As the narrative progresses, Naomi remains an object, even appearing completely nude before the camera, posing against the door of her bedroom seductively in a long shot in the next scene we see her in after a date with Jordan. After this point, we only ever see Naomi within relation to Jordan, painting her existence to the audience to revolve solely around Jordan rather than really ever having her own defined personality other than being his trophy wife, leaving her entire character to be conveyed to the audience as nothing more than an object throughout the entire film. The sidelining of Naomi in the production could be suggestive of Scorsese's own opinion of her character and overall role in Jordan's life and success, which is where Scorsese has come under fire by critics, who claim that the film caters solely to the 'male gaze', this degrading attitude towards women, and Jordan's overpoweringly obnoxious and deceitful behaviour in "Wolf" could be seen to be reflective of the atmosphere of life on Wall Street, with the autobiographic novel by Belfort himself which shares a title with Scorsese's treatment displaying the same narcissistic, objectifying and obnoxious personality traits in Belfort as he glorifies himself and his antics by seductively twisting them into a black comedy; this display of narcissism. "Psychological projection involves projecting undesirable feelings or emotions onto someone else, rather than admitting to or dealing with the unwanted feelings" (Emotional Health, 2018). This defensive projection, which is often subconscious, relates to protecting an individuals feelings of ego and self-worth according to Freudian perspective, and more recent studies propose that "projecting a threatening trait onto others is a byproduct of the mechanism that defends the ego, rather than a part of the defence itself. Trying to suppress a thought pushes it to the mental foreground (...) and turns it into a chronically accessible filter through which one views the world" (Kim Schneiderman, Noam Shpancer, Patrick Heck, Seth J. Gilliham, 2018). This is a trait which I find to be conveyed particularly clearly through Scorsese's overall treatment of Belfort and is brought to life by DiCaprio on screen; a scene which I feel portrays this defensive projection particularly well is towards the end of the film, when Naomi (the previously mentioned 'trophy wife') tells Jordan that she wants to divorce him. Both characters lay across the bed horizonally in this scene having just had sex, again a signification of Naomi's objectification, dominating the forefront of the screen so that the audience clearly sees both character's responses and expressions to the conversation that is taking place. "You don't love me? You don't love me anymore? Well isn't that just fucking convienient for you, now that I'm under federal indictment, with an electronic bracelet, now you don't fucking love me anymore" (The Wolf of Wall Street, 2013). This particular quotation from the dialogue in this scene displays clearly a sense of fragility and insecurity radiating from Belfort's character, rather than engaging in a meaningful and logically minded conversation allowing Naomi to express her reasoning, Jordan, here , is taking what he is most insecure and uncomfortable with and projecting that onto his wife. He is assuming that his poverty and the embarassment of criminal indictments and jail time is to blame for the failure of his marriage, rather than putting aside his narcissism and realising his own maltreatment of Naomi throughout their years of marriage. Scorsese's choice to display Jordan as self-pitying, hard done to, and almost vulnerable in this scene almost acts to make us side with him in the scene, as a man who has lost everything rather than with Naomi who appears to be crazed, cold hearted and borderline cruel, which could be seen to be oppressive and sexist in terms of Scorsese's own views. Whilst this scene, just like many others in the film could be viewed as incredibly oppressive and misgynistic, as it allows the audience to feel as if Naomi is deserving of the scenes of blatant domestic abuse as the situation develops, however I feel that Scorsese auteured this particular scene in order to highlight the depth of Belfort's narcissism, manipulative behaviour and selfishness as DiCaprio subtly but successfully shifts the feeling of blame from his character to Robbie's , we are encouraged to see Belfort for the notorious scam artist that he truly is- albeit a message that is clouded for some by the ferocity of the scene itself.

The narrative of Scorsese's "Goodfella's" (1990) differ's entirely to "The Wolf of Wall Street"'s, taking us back to the gritty roots of Scorsese's upbringing as we follow the life of Henry Hill and his involvement in the Italian Mafia in New York. This in itself I feels allows for many examples of fragile masculinity to come through the lens as the film itself begins in 1955; in contextual and historical terms, this era held a much more hostile view towards women, with the cold war ocurring women were expected to uphold the household and their wifely duties. Popular culture and the media at the time reinforced traditional gender roles, and the ideals of domesticity reflective of the american dream, "the term nuclear family emerged to describe and encourage the stability of the family as the essential building block of a strong and stable society" (Khan Academy, 2016). This is projected by Scorsese from the beginning of the film, where Henry is depicted as a youth to the audience, appearing to be constrained and ruled by his mother and family life, even being beaten when his father comes into the knowledge that Henry has been skipping school in of at his 'cafe' job. The control his mother holds over family life, and her submission to his father in early life, such as when Henry's mother's protests to him beating Henry were met with blatant ignorance and eventually for him to turn on her. Freud proposed in his theories that "childhood experiences shape our personalities and behaviours as adults" (Lumen Learning, date of publication unknown), meaning that these early reflections on the woman's role in a nuclear family throughout childhood and the fragile masculine trait for a man to be completely dominant over his wife and his household would have most certainly played a significant role in Henry's perspective on women later on in life, which is a trait that I feel Scorsese accurately conveys, whether intentional or not, throughout the remainder of the film.

Henry's perception on the woman's role in life and his objectification of women throughout the remainder of his life on screen is obvious and evidently influenced by the people that he surrounds himself with, such as Jimmy and Tommy, both of whom objectify and degrade women openly on screen. The audience first experiences Henry's misogynistic values when he goes on his first date with Karen, played by Lorraine Blacco; the scene the audience witnesses is a double date between Tommy, his girlfriend, Henry and Karen, the exchange is awkward, and the monologue that Scorsese chooses to add in a voice over fashion in the editing process provides us with the innermost thoughts of each character, as if we as the audience are being addressed as the subconscience, thus creating a subtle break in the fourth wall, a feature which goes against basic cinematic 'rules' by asking the audience to think critically and engage on an individual level with the picture they see before them which incorporates them into the story rather than allowing them to view the story as if they are a spectator. In this scene, the camera sits at medium range to the compositions, meaning that their heads and torsos are in the shot as they are seated around the table for dinner. Henry is preoccupied with other engagements, paying no mind to his company as he dines, appearing rudely disinterested to the audience as he engages almost sarcastically in small talk with Diane and Tommy, being wholly cold towards Karen throughout the duration of the scene. Henry's disrespect towards Karen in this scene although downplayed is significant in the following scene, as Karen confronts Henry for standing her up on a second date. I want to focus particularly on this scene due to the fact that it draws attention to the fact that for a woman to be respected she had to assert herself, and to a certain point this is evident in this scene.

"Henry: (voice-over) I remember, she screaming on the street, and I mean loud, but she looked good" (Martin Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi, 1990), in itself, this piece of script conveys fragile masculinity on behalf of Henry through the enjoyment he finds from holding power over women, and pushing them to the point of assertion, and can also be related to Laura Mulvey's theories on the male gaze, as in this situation, rather than focusing on the words that Karen is speaking, the voice-over invites the audience to view her as an object of sexual gratification or aesthetic pleasure rather than as a human being, which she eventually submits to, agreeing to let him take her out again. In this scene, multiple of Henry's fellow gang members surround him, all of them laughing, but rather than in support of Karen, this is done to suggest that they are in fact laughing at her behaviour, and the fact that Henry is standing for her verbal barrage of abuse on the street, which explains his haste to solve the disagreement. I find this to be particularly clever on Scorsese's part as a director, as he is building our relationship with Karen as the submissive, dutiful wife from the onset of their relationship, also indicating the misogyny that was inherent within society in that particular era, which proved to be a highly controversial and debated topic.

Another scene which I would like to draw attention continuing from Henry's lack of respect and overall inherently misogynistic values is when Karen wakes Henry up to a loaded gun pointed straight at his face having found out that he is having an affair and being pushed to breaking point. At this point, we see directly through the lens the affects of Henry's years of maltreatment, a woman driven to hold a loaded weapon to her husband's head because her entire purpose, being his trophy wife, has been stripped from her. Although unintentional, by following the perspective of Mulvey's 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema', we can assume that the intent is that without her purpose of being her husband's home-maker and haven, she is perceived both by the camera and by society at that point in time to be purposeless and almost crazed as she appears before the lens in a close-up, point of view shot detailing her sleepless, mascara stained face as she shakily holds the gun. This fleeting moment of power, however, is swiftly removed as she is overpowered by Henry and then beaten into submission, thus affirming his internal monologue that his shortcomings can be overcome by overpowering those who are the most vulnerable in his life, an ethic which follows into his work, and highlights his tendency to ignore his flaws and wrongdoings; emotional stoicism is heavily linked to fragile masculinity, and the ideal that "though you can't prevent these emotions, you could could convince them (an individual) that hiding their feelings is the very essence of manhood"(Ilan Shrira, 2016). Henry's refusal to acknowledge his dissatisfaction within his relationship leading to his unfaithfulness and his overall narcissistic and objectifying nature towards most of the women in his life throughout the production could therefore be seen as a reflection of Henry's own shortcomings and guilt and as an individual, albeit very subtly.

Upon analysis I find that both productions do quite clearly convey instances of fragile masculinity, most of which relate to either the narrative itself of builds context within the eras that they are shot in and in the values that the films represent. Despite many critics disagreeing with this sentiment, I find that through the lens, Scorsese is able to accurately convey the morals and ethics surrounding the narratives that he was directing and their contextual relation to their given eras. 'The Wolf of Wall Street', although highly explicit in sexual content and frankly derogatory scenes, tells the story of Jordan Belfort in both an accurate and amusing delivery, and 'Goodfella's' follows the same sentiment, staying true to Scorsese's roots and growing up as an Italian-American in New York. Inherently within the production of his films, Scorsese holds certain opposable views, such as his recent statements on writing lead female roles who hold value to the plot aside from being the pretty, trophy wife. "That goes back to 1970. That's a question that I've had for so many years. Am I supposed to? If the story doesn't call for it then it's a waste of everybody's time." (Martin Scorsese, 2019); this could be seen to relate to Scorsese's own childhood,the era that he was brought up in and their retrospective view of women and their role in life and in the film industry in general and could conclusively be viewed as a reflection of his opinions and the world that he himself grew up in on screen on first glimpse. However, drawing from the fact that the majority of his productions have scripts which are often outsourced and then amended for the screen, I'm not so quick to agree that this is necessarily the truth or whether this display is a projection of Martin Scorsese's opinion in this instance, but rather a 'mise-en-scene' to his productions, contextually mirroring the times in which they were set, and in the case of 'The Wolf of Wall Street', to remain true to detailed autobiographical events, even to the extent where Scorsese had Leonardo DiCaprio spend time with Jordan Belfort so that he could effectively mirror his narcissistic and overwhelmingly self-inflated personality on screen.

In conclusion, although both 'The Wolf of Wall Street' (2013) and 'Goodfella's' (1990) clearly display instances which could be perceived through the psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud, Jacques Lacan and Laura Mulvey to point towards the representation of fragile masculinity on Scorsese's own behalf, and could be seen to be widespread and deep rooted throughout his productions, with many of them coming under deep scrutiny for the role and treatment of women and the abuse of drugs and other substances throughout. However, \I find that this scrutiny could perhaps be drawn from biased conclusions, as within relation to both the eras that the films were set to span over and to the novels that each film is based on, the films both accurately represent both their original authors, and the social climate around gender roles and the role this played on fragile masculinity as a whole; I feel that rather than participating in this degradation, Scorsese is mocking it, aligning with the dark humour that is prevalent throughout both films, and this has been misconstrued for being Scorsese's own fragile masculinity being conveyed through l'auteur theory (a theory founded in the french cinematic new wave whereby the director uses the camera as a pen to express his thoughts) due to over analysis and close inspection of Hollywood production since the beginnings of the 'Me Too' movement in

2016 which saw hundreds of women come forward against abuse orchestrated by big production studios and their directors such as Harvey Weinstein, and although this is highly relevant and should be discussed within mainstream media today, this should not affect the way that we view individual directors and their art.

Bibliography

- Cherry, K., (2019), "Freud's Theory of the Id in Psychology", Very Well Mind, available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-id-2795275

- Emotional Health Editors, (2017), "Psychological Projection: Dealing With Undesirable Emotions" published by 'Emotional Health', available from: https://www.everydayhealth.com/emotional-health/psychological-projection-dealing-with-undesirable-emotions/

- Gervais, R., (2020), "Ricky Gervais at The Golden Globes 2020", available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sR6UeVptzRg&t=2s

- Scorsese, M., (1990), "Goodfella's",

Comments

Post a Comment